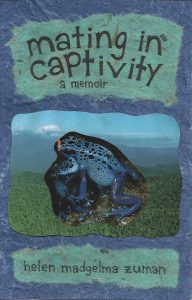

While we love to focus on the positive side of intentional living here at FIC, we also know that communal living, when taken to its extreme, can become, well, a cult. A new memoir by Helen Zuman tells the story of the years she spent at Zendik Farm, where relationships were orchestrated and overseen by the community matriarch. She “split up lovers who grew too close, warning sexual corruption would lure us to betray the revolution. Dissolving into her panopticon, I surrendered love after love – only to suffer a brutal drop from grace that forced me to face Zendik’s contradictions and start, at last, on a story of my own.”

Mating in Captivity serves as a timely reminder that not all communes are what they seem – and it’s important to do research before joining one. Read an excerpt from Chapter 1 below, and support the project on Kickstarter to get your own copy!

****

Chapter 1 – Interview

Chapter 1 – Interview

I began spinning a fantasy about Zendik mating the night I arrived.

Cross-legged on the living room floor, a metal bowl nestled in my lap, I watched a short, round woman with buoyant ringlets burst in from the kitchen, bowl in hand. Another woman called to her, across the room: “Are you having a date tonight?”

Between them lay a sea of Zendiks; maybe two-thirds of the Farm’s sixty-plus members filled every chair, couch, and patch of rug. The lemon scent of Murphy’s Oil fused with the glow of standing lamps to bathe us in resinous incandescence.

Forks clanged against stainless steel. Chatter rolled past me like delicate thunder.

The short woman nodded, her face erupting in a joyous grin. I felt a prick of envy. It must be so lovely, I thought, to go out for dinner and a movie with a guy you like, then return, in cricket-quiet, to this cozy old Farmhouse. Never mind that none of the handful of dates I’d been on – all as a teenager in New York City – had involved dinner and a movie. This was Polk County, North Carolina. The sticks. People here must mimic the mating behavior of characters in Sweet Valley High books and Archie comics. I wondered why the woman going on the date had gotten food for herself. Wouldn’t she be eating out, with her boyfriend?

I took another bite of brown rice and pinto beans, topped with fresh salsa. I snapped off the sweet white stem of a leaf of romaine. I was eating the same food as the others. But the bowl I ate from, the fork I ate with, set me apart. They warned that Zendik warmed as you pushed towards the center. I was at the outer rim. I would have to earn my way in.

Minutes earlier, a graceful young woman named Eile had shown me to the shelves where bowls, plates, mugs, spoons, forks, and knives were stored. I was to pick one of each and mark it with my name, in felt-tip pen on masking tape. “You’ll be on quarantine for ten days,” she said, “which means you can’t cook or wash dishes or eat from the same dishes we eat from.”

“Okay,” I said, feeling as though I’d just broken out in sores only I couldn’t see. No commune I’d visited before Zendik had placed me on quarantine. Eile shrugged in apology. “It’s just that we live so close to each other,” she said. “If one of us comes down with a bug, everybody gets it.”

I folded the rest of the romaine leaf into my mouth. Eile joined me on the floor. “So how’d you find out about Zendik?” she asked.

“I saw it in The Communities Directory.” The Directory was an encyclopedia of well over a thousand groups, most in North America, most devoted to homesteading. I’d ordered it the previous winter and pored over it in my Harvard dorm room. The next spring, just before graduation, I’d won a thirteen-thousand-five-hundred-dollar travel grant to spend a year visiting a few of these communities.

My grant proposal wasn’t the first stage in a master plan. I had no master plan – only a couple tropisms: away from school and jobs, toward being outside and touching what was alive. After eighteen years in classrooms, I yearned to put my body to work, as something more than a dolly for my brain. To learn sources of food, water, warmth, and shelter, beyond “the supermarket,” “the tap,” “the furnace,” and “the landlord.” I sought a story broader and sweatier than the one I’d grown up in. Touring villages rooted in the back-to-the-land movement seemed like a good start.

By the time I arrived at Zendik, on October 26th, 1999, I’d stepped into a few communal stories, none strong enough to hold me for long. I’d spent three weeks at the Reevis Mountain School of Self-Reliance in the Superstition Mountains near Roosevelt, Arizona, where the ruling couple seemed pleased with their seclusion and the only other intern left before I did. A day and two nights at Alpha Farm in Deadwood, Oregon, where I was told to sit in the garden and give it my “love energy” (subtext: we’re overwhelmed by our own chaos; we can’t help you with yours). A night at the San Francisco Zen Center’s Green Gulch Farm in Muir Beach, California, whose dense fog of patience made me wonder where people buried their snarls, their irritation, their hatred – and where, if I lived there, I would bury mine. Back home in Brooklyn I’d taken the ferry to Staten Island for Friday-night dinner at Ganas, where most of the men were pale or gray-haired and the aim of the full-group mealtime discussion – an example, I was told, of “feedback therapy” – seemed to be to elicit bewildered, angry tears from the two women at the center of the ring. Soon after that I’d sold myself on visiting Zendik – using its Directory listing, its fledgling web site, and a phone conversation with Zylem, the veteran Zendik in charge of recruiting. Then I’d boarded a Greyhound bus to Hendersonville, North Carolina. A couple Zendiks had retrieved me from the depot after completing the Farm’s weekly shopping. I was loosely planning on staying two weeks.

When I mentioned The Communities Directory, Eile’s eyes lit up. “Really?” she said. “Me too! But I think we’re the only ones. Most people showed up because of the magazine.”

I’d flipped through my first Zendik magazine earlier that evening, in the back seat of the car that had brought me to the Farm. I’d zeroed in on a story by a woman named Karma about a Zendik road trip to Woodstock’s corporate reincarnation in the summer of 1999.

“You guys go on road trips to hand out magazines, right? Like that trip you took to Woodstock?”

“Yeah,” said Eile. “We go out most weekends. When the concert scene is slow, we sell the street.”

I could tell that “sell the street” meant “sell merchandise on the street.” What threw me was the word “sell.” “So you don’t just hand the magazines out? You sell them?”

“Yeah, that’s how we support ourselves. We get donations sometimes, and apprentice fees, but they’re not reliable. Selling is our survival.”

Selling for a living sounded intriguing – but I doubted I could do it. Once, I’d spent an afternoon distributing free copies of The New York Observer on a busy corner in Soho. I’d crumpled under the neutral cruelty of brush-off after brush-off, while my partner, laughing and bantering, had rapidly emptied his satchel.

“Does everybody go selling?” I asked.

“No, not everyone. I mean, almost all the girls do, every other weekend or so. But some of the guys aren’t that good at it, so they only go out once in a while.”

As Eile spoke I noticed a bright fringe of scarves, shirts, and sweaters trimming the rail of the loft above the living room. “What’s up there?”

“That’s where a bunch of the girls sleep. We just moved in a couple weeks ago. The guys don’t mind the draft in the barn, but for us it was getting to be too cold at night.”

Uphill from the Farmhouse, at the end of a wide gravel path, stood two barns – one for horses, one for goats. Before dinner, Eile had led me up the hill, pointing out studios for music and dance, a wood shop adjoining a trash shed, a storage yard for building materials salvaged from demolition jobs in nearby towns. Then I’d followed her up a steep, rail-less staircase to the horse barn loft. A few dozen bunks lined the loft’s long sides. Wind slipped in through gaps between wall slats. These bunks slept most of the Zendik men.

At the back of the loft stood an insulated plywood box, about eight feet tall and twice as wide. Half of the ten bunks inside the box belonged to a motley crew of strange males who, like me, were “new people.” These would be my roommates.

Sitting with Eile in the living room, admiring the gaily decked railing, I wished I didn’t have to trek up to the barn in the dark. I wondered what would earn me a bed here, among women.

****

Read more from Chapter 1 here and check out its Kickstarter page to get a copy!