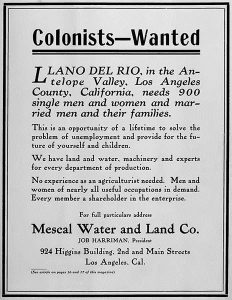

“Colonists–Wanted,” the ad proclaims. “Llano del Rio, in the Antelope Valley, Los Angeles County, California, needs 900 single men and women and married men and their families. This is an opportunity of a lifetime to solve the problem of unemployment and provide for the future of yourself and children.”

“Colonists–Wanted,” the ad proclaims. “Llano del Rio, in the Antelope Valley, Los Angeles County, California, needs 900 single men and women and married men and their families. This is an opportunity of a lifetime to solve the problem of unemployment and provide for the future of yourself and children.”

It almost sounds like something you might find in an ad for an intentional community today–except maybe for the sheer size of it, or the more traditional gender roles. But the Llano del Rio colony began over a hundred years ago, in 1914. It was the brainchild of Job Harriman, a Los Angeles lawyer who had earlier run as a Socialist candidate for Vice-President on the same ticket as Eugene Debs.

Frustrated with the politics of the day, Harriman set out to create a socialist utopia. He purchased 10,000 acres of land in the Antelope Valley, a sparsely-inhabited region of California just north of Los Angeles and west of the Mojave Desert. Launched in May 1914 with just five families, it quickly grew to welcome over 100 colonists and a handful of barnyard animals.

Harriman put out ads in socialist newspapers, hoping to attract “idealistic” and “industrious” families to leave behind urban poverty and embrace a rural lifestyle. The community was highly selective; prospective memberships had to offer three references and answer a questionnaire with prompts such as: “Will solving the economic problem ultimately lead to solving the social problem?” “Is happiness a state of mind or dependent upon affluent material conditions?”

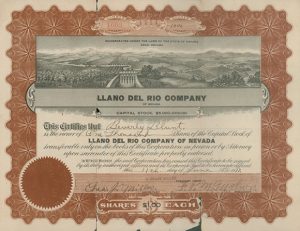

Like similar communes of its day, the Llano del Rio collective was a joint-stock company. According to Kim Stringfellow at KCET:

Like similar communes of its day, the Llano del Rio collective was a joint-stock company. According to Kim Stringfellow at KCET:

“Llano del Rio Company required new members to invest in the colony through a joint stock venture — $500 cash was required upon acceptance towards a fixed 2,000 shares valued at $1 each, payable over a six-year period. Members were paid to work on-site for $4 per day with $1 going towards the purchase of outstanding stock shares. The remainder went towards collective daily expenses such as meals and lodging. Workers’ contracts stated that any future profits were to be credited to each investor’s account, a promise that never actually materialized.”

Within several years, nearly 1,000 people lived at Llano del Rio. It had grown into a fully-functioning village that produced 3/4 of its own food and necessities on site. There was a quarry, sawmill, and kiln; a soap factory, cannery, and dairy; a post office; and even a Montessori school. Residents entertained themselves with music, dancing, and sports. Stringfellow writes:

“Architect Alice Constance Austin proposed a conscious feminist design for the future Socialist City that featured a nongrid circular spatial plan with centralized communal kitchens, laundries and daycare, built-in furniture, and other modern innovations that minimized housekeeping while relying heavily on modern technologies such as electricity. Women were meant to equally participate everyday governance and politics of Llano. Freeing them from daily toil of ‘woman’s work’ was the first step in doing so.”

But after a few years of growth, the colony ran into difficulties. Residents lost their water rights to nearby ranchers. Some left to join the war effort. A duplicitous investor nearly bankrupted the joint-stock company.

The colonists struggled to maintain their egalitarianism amid the rampant racism of the time. Advertisements for new colonists called for Caucasians only–not because of “racial prejudice,” they claimed, “but because it is not deemed expedient to mix the races in these communities.” Other homesteads that welcomed African-Americans were situated further east in the Mojave Desert.

As the colony fell apart, and Harriman found himself under attack in the press, he and some of the colonists moved to Louisiana, where they formed New Llano. This lasted until 1938, though it never reached the size of the original colony.

Today, all that’s left of Llano del Rio are a few stone foundations in the Antelope Valley. But the history of the colony serves as a reminder that even the most progressive communities have their blind spots. As we work to address racism and classism in our communities today, we can learn from the mis-steps of communes like this one – and we can make sure that we don’t replicate their exclusionary language in our own ads for new recruits.

****

Photos from “Double Look at Utopia: The Llano del Rio Colony,” Aldous Huxley and Paul Kagan (authors), California Historical Quarterly, Vol. 51, No. 2 (Summer 1972), 117-154.