4 weeks and 6 communities later

My first cross-country communities tour of the year ended with a 3 day training on Tools for Collective Self-Governance in Oakland, CA with the Nonprofit Democracy Network. I got to spend 3 days with a bunch of badass organizers working for awesome organizations trying to make the world a better place for everyone. It was an ideal place to synthesize what I’d been learning from the different communities I’d visited, and to explore some of the pressing questions the FIC has been grappling with in our desire to both grow and refocus the movement.

I see my role as Executive Director of FIC as being a kind of switchboard, and also as a synthesizer. When I’m visiting communities, at events, or working on group projects I try to do a lot of listening and asking questions. I listen for commonalities and themes in what people say and try to mash it up into something coherent. I don’t think I deserve credit for any of the ideas I express. I’m just trying to help us all be in synch so we’re moving forward together. I’m grateful to all the people I get to work with and interact with, all of whom are my teachers.

This post is a companion to more of a report on the ideas from training, which you can find here.

Two memories stand out that helped form my understanding of intentional community.

I was 19, new in a communal kitchen that had a kitchen cleaning system, and asked a wise older communitarian for clarity on what things I needed to clean and what I didn’t. She named a couple of the norms, and then said, just try and leave things a little cleaner than how you found them. I remember at the time feeling like someone had grabbed my brain and sharply turned it. Viewed as a practical summation of a life philosophy or paradigm, I’m still trying to understand the implications.

When I asked another wise older communitarian about why intentional community matters, she said, we’re here together, sharing finite resources, and trying to figure out how to do it without killing each other, isn’t that what the world needs to learn? Again, mind blown.

For me, intentional community isn’t an end in itself. I was raised with a sense of responsibility as a global citizen to help make the world a better place, and intentional community has been the path I’ve chosen to fulfill that.

When I started working for the FIC, I framed it with a core question: How is intentional community relevant and applicable? Over the last 3 years this continues to be my guiding inquiry.

What is being learned in intentional communities that is relevant to larger society and how can it be applied? And conversely, what is at play in larger society and how can intentional communities work with that more? I want to take what’s being learned in them and share it with the rest of the world.

Intentional communities in themselves are not going to end climate change, racial injustice, or political corruption, but they are places where these systemic issues humanity is dealing with on a global scale can be explored and addressed in a holistic way at a human scale. Not that the problems aren’t at a human scale too. But they are global, and it’s overwhelming to think about change on that scale. But at some point we have to, because we’ve set the world on fire and it could kill us.

We are going for nothing short of global transformation. Our North Star needs to be beyond carving out these niches within an unsustainable system. We live in a society that seems to have a death wish, and for all our efforts at creating communities where something different is happening, we’re still going down with the ship. And we only get to do our thing because it’s not expedient for the system to assimilate us, and only as long as we play by certain rules.

We want a world where oppression and exploitation of people and planet is simply not considered, because it is fundamentally recognized that harm to one is harm to all. Like, why would you do that? We are learning that “my” liberation is tied up in “your” liberation, and that no matter where you are on the scale of privilege to oppression, we are all traumatized by this system. We also have to be pragmatic about the realities of the world we live in right now, manage our day to day lives, and figure out how to take doable steps in that direction.

Intentional community provides an access point, as do other forms of cooperative organization that are working to shift the culture and systems that underlie social and economic relationships, and the relationship between people and the planet.

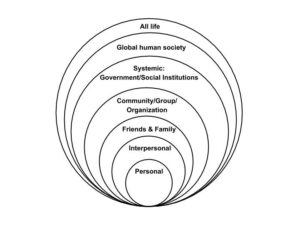

These relationships operate on lots on levels, which different groups have visualized with concentric circles. Here’s a modified version based on what the Nonprofit Democracy Network (NPDN) offered at the training:

Organizations are in the middle, where you can access the personal and interpersonal as well as see how things scale outward to global human society and all life.

Looking at intentional community as a particular form of community/group/organization, what does the intentional part of intentional community mean? I think it means that the “we” part of the community have some degree of unity about what our intent is, how we want to move forward together in time and action in the creation of our shared society and its relationship with the world around us. There’s a shared awareness, a common understanding, which is codified in a system of governance that is organizing the community to manifest that intent.

What if a global human society could see itself as a community and set a collective intent to share this planet sustainably and peacefully? I’ve heard it suggested that one of the big steps in that direction came when the first images of the entire planet came back from space. It provided the first tangible affirmation that this (planet) is it and we’re all (all humans and all life) in this together.

I’d like to think we’re heading in the right direction. Wage slavery is certainly better than chattel slavery, but it’s still part of a system that legitimizes the dispossession and disenfranchisement of people from their ability to access the resources needed to survive. Essentially, it’s still legal to kill people. It’s also legal to extract resources and produce waste that poses a threat to the ability of ecosystems to sustain themselves, which has become one of Earth’s biggest extinction level events and has the potential to make the Earth uninhabitable for humans without major technological intervention.

The thing is, and this is where it gets really overwhelming, where we’re trying to go has to include everyone. No really, everyone. Everyone needs to be on board. Every human being. And we have to consider the rest of life of on the planet. How do you even begin to comprehend that level of decision-making process? Is it even possible?

I think we have to believe it is, and this is where I think intentional communities have something to offer, because getting everyone on board is part of what you have to do in intentional community. It’s hard enough to do it with a small group, let alone with 7.5 billion people. But we have to start somewhere and scale up. There are examples out there of larger scale consent-based decision making. The uprising in Seattle against the WTO in 1999 showed that coordinated action amongst tens of thousands of people using a consensus based, spokes-council model was possible.

One of the things we know is that the process is as important as the outcome.

At the NPDN someone threw out the idea of “sense-making.” I reminded me of what someone I interviewed said about the Quaker understanding of consensus, that it was about getting the “sense of the meeting.” I understood it as a kind of precursor to decision-making. The classic situation in consensus is when someone jumps to making a proposal before the group has really talked through the problem, there’s immediate push back, and you get stuck in a “this or not-this” argument.

If we’re going to make a truly collective decision about what to do, we’re going to need to have a collective understanding of the situation. We need to make sense of something before we can decide what to do about it. My take on Occupy was that this was a key part of what was trying to happen in that movement, and why it was so hard to say what it was about. Occupy was trying to get everyone to the table, on a level playing field, so we could begin to collectively understand the problems we were dealing with and figure out collectively what to do.

Intentional communities are fundamentally about relationships, relationships of sharing. At the NPDN, someone asked the question, what if the core of what we’re doing is building trust?

Sharing requires trust, trust requires intimacy, intimacy requires vulnerability, in the emotional sense. Another side of vulnerability is about being vulnerable to something. The idea of collective liberation has to do with making sure the most vulnerable among us are cared for, and, in today’s world, defended.

We need to make ourselves vulnerable to each other if we are going to be able to trust each other enough to share with each other in a sustainable and equitable way. There’s a deep irony in the obsession with independence and individualism in society. The American Dream is a key story behind this obsession.

We’re taught to value and pursue financial independence in particular. But financial independence means we have all the money we need to buy the goods and services we want. But if there were no goods and services, what good would the money do us? How long would most people last in the wild, or even on a farm? We are so utterly and completely dependent on each other, perhaps more so that ever before, and yet the entire world view of the dominant system tells us otherwise. We need to be vulnerable about the fact that we are vulnerable without each other.

Belonging is a core concept I’ve been hearing brought up repeatedly. There’s something core about intentional communities here. Who is a member? Who is part of the group? This leads to a whole mess of dynamics around acceptance/rejection, inclusion/exclusion, who’s in and who’s out, and why, and who gets to make the decisions.

At some point in human history this was matter of survival. Even before civilization, odds of survival were better as a group, and shame, shunning, and exile were methods of maintaining group coherence. Maybe this is a little melodramatic, but, deep in our bones, belonging is survival. But our needs as humans don’t end with survival.

Belonging is meaning. We need each other to understand who we are, and we need to understand who we are to be able to get out of bed in the morning.

The dominant institutions, infrastructure, and culture in our world are designed to create isolation, disempower communities, and extract resources at dangerously unsustainable rates. The pursuit of individualism and consumerism is tearing us apart and driving us to the brink.

Our response is to create a movement of decentralized, interdependent, cooperative communities that can thrive in adverse conditions, rebuild our social fabric, and bring us to a cooperative, just, and sustainable human society.

We are relearning we.